Home » Swapping signals for ramps may be best pick for Richland gridlock

Swapping signals for ramps may be best pick for Richland gridlock

November 14, 2019

Richland council to review final traffic report at Dec. 3 meeting

Richland is close to deciding the best way to improve traffic flow and reduce congestion for drivers moving north and south through the city.

The top-ranked project calls for removing a number of traffic signals at intersections along the bypass highway. The final proposal, which will include comments from an October open house and online survey, will be presented to the city council for approval on Dec. 3.

The city prioritized traffic options using nine weighted criteria, with the highest value given to safety, followed by human impact, like noise or effect on homes, and then cost. The least value was for reducing delays on side streets.

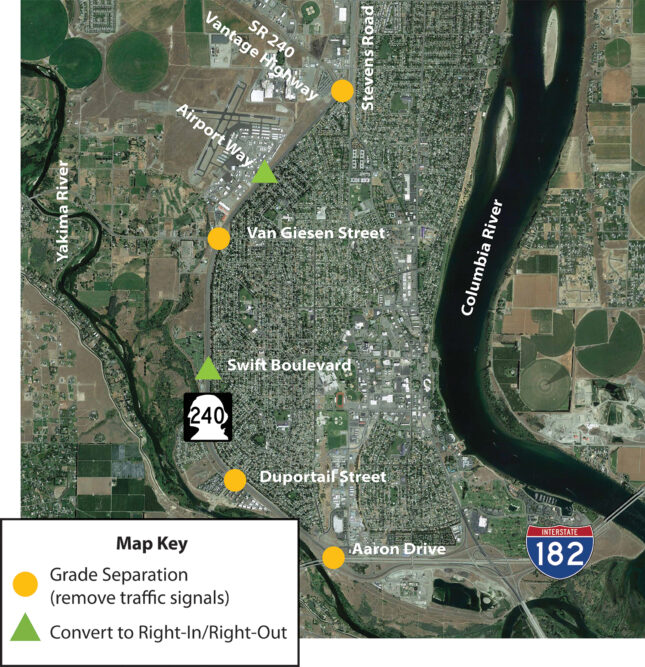

If the project suggested to the council recommends eliminating traffic signals, they would be replaced with “grade-separations,” which would look like freeway interchanges with ramps and overpasses.

It’s estimated to cost $132 million to remove traffic signals and build interchanges on the bypass at Aaron Drive, Duportail Street, Van Giesen Street and the Vantage Highway/Highway 240.

Projects received a priority ranking from 1 to 7, with the possibility of doing nothing at all falling at No. 5 in the lineup.

A project considered the second priority is actually wrapped into the first priority. This would be to re-do the intersection at Aaron Drive, Interstate 182 and Highway 240 at the south end of the bypass. It’s listed as a standalone project, but also as one of the intersections where lights would be removed under the project currently at the top of the list.

Pete Rogalsky, public works director for the city of Richland, explained why the two separate listings exist at the recent open house: “No. 2 has been called out as the most promising, the most effective, the easiest to implement of the things within No. 1, and so it’s been called out separate to give it the visibility that the way to start on No. 1 is with No. 2. But it isn’t really a separate thing.”

Other intersections on the road would be converted to only allow right turns in and out, including those at Swift Boulevard and Airport Way.

The city already applied for a federal grant seeking $29 million to create a “flyover” at Aaron Drive that’s basically a bridge allowing southbound travelers to avoid stopping at the current three-way intersection.

The grant would cover 80 percent of the expected cost of the project. Richland expects to find out before the end of the year if it is approved.

Other recommendations have some residents concerned, including option three, which calls for improvements at George Washington Way and Columbia Point Drive.

It has Tri-Cities Academy of Ballet & Music owner Joel Rogo worried about his studio being in the city’s “crosshairs.”

“The three options that I fought four-and-a-half years ago are still on the city’s website. The city voted a resolution that staff was to find a fourth plan that didn’t affect the Ballet. I’m named in the resolution, but nothing’s been done,” he said.

Even if the city plans to chase money for another project as its first priority, Rogo is no less comforted.

“Yes, it’s option three, but it’s the least expensive and they have no other options for that area,” he said.

He’s got reason to worry. Rogalsky said $12 million in improvements to George Washington Way could be completed through more readily-available grant programs, which aren’t a possibility for the projects listed first and second.

“That one could be chipped away with annual, or every-couple-of-year grant programs, and you could, over time, assemble the money and not require legislative action,” Rogalsky said.

It’s why Rogo asked the community, and especially ballet families and supporters, to attend the October open house, complete the online survey and insist that any George Washington Way improvements not affect his business at 21 Aaron Drive.

“I don’t want to be blindsided, so I want to keep reminding the city that I’m here. As soon as they come up with a plan that doesn’t harm the Ballet, or say they won’t affect me, we’ll back off,” he said.

The recommendation least likely to be suggested to the council as a priority, but still popular with many of the more than 150 people who attended the open house is a plan to build a bridge over the Columbia River in north Richland, about a mile north of Horn Rapids Road. It would allow travelers to head east across the water, connecting to Columbia River Road and eventually to Road 68, both in Pasco.

Both at the October open house and a separate open house hosted in March by the state Department of Transportation, a number of commuters shared their support for the bridge, despite the hefty price tag likely to sink its prospects.

“The bridge fell to the bottom because it’s a tremendously long horizon,” Rogalsky said. The bridge likely would to take up to 20 years to build, at a cost of up to $450 million, and include widening Road 68 south to Sandifur Boulevard to accommodate more traffic.

Compare this cost to Richland’s new Duportail Bridge, expected to open next year, that will cost $38 million.

An inexpensive alternate that fell toward the bottom of the list would be to add a single lane southbound on the bypass from north of the Vantage Highway to Interstate 182, a project estimated to cost $25 million.

Walkability advocate Laila Krowiak wants the city to focus on moving people, not cars. She urged the city to prioritize cyclist and pedestrian safety, though the city is not yet at the design phase.

“I would like to see it acknowledged that as the area grows, congestion will always be a problem, no matter how wide we make our streets. We can look at California. The wider the streets are, the congestion is still there. Instead of focusing on helping congestion, we could focus on giving people different options for transportation. If we make roads wide and fast, people don’t have any other options, they have to drive. Even if they’re going a couple miles, they have to drive,” she said.

Representatives from Richland, West Richland, Benton County and the state have worked with a team of consultants to study the challenges faced by drivers headed north and south through the city, with an ultimate goal of finding a project most likely to reduce travel times.

Most specifically, the team focused on three north-south corridors: the bypass, George Washington Way and a new connection on Kingsgate Way between Keene Road and the Vantage Highway.

The recent open house and online survey are considered an extension on work done in the Highway 240 study by WSDOT that looked at improving mobility on 240 specifically, along with an update to the regional transportation plan. The timeline for the current work taken on by Richland began in April with the research phase and is expected to conclude by the end of the year with a recommendation to the council.

“The most impactful decision that they will make will be to authorize chasing money for one or more of the recommendations,” Rogalsky said.

Still, Rogalsky said the No. 1 and No. 2 projects are both “beyond the city’s capacity to do” and beyond what routine grant programs would cover.

But it’s important to have the priority in place for potential state or legislative action. Washington last made its big investment in transportation in 2015, authorizing $16 billion in spending.

With the passage of Initiative 976 in the Nov. 5 election, city and county officials across the state are bracing for how it could affect their local road projects.

The initiative limits car tab fees to $30 for vehicles that weigh 10,000 pounds or less. Fees more than $30, which vary based on where a car is registered and the type and weight of vehicle, will be eliminated or reduced. Money from car tab fees goes toward state and local transportation projects, as well as highway construction and maintenance.

Gov. Jay Inslee said it’s clear the majority of voters objected to current car tab levels. “I have directed the Washington State Department of Transportation to postpone projects not yet underway. I have also asked other state agencies that receive transportation funding, including the Washington State Patrol and Department of Licensing, to defer non-essential spending as we review impacts,” Inslee said in a statement.

The state plans transportation projects at 20-year intervals, trying to predict how many people will be in the region at that time, where they will live and where they will work.

“You want to aim at a long enough horizon to be meaningful because it takes so long to do these things, so if you aim for a shorter horizon, then you would get swallowed up by the trends,” Rogalsky said.

Even if money weren’t an object, the goal isn’t necessarily to complete every option on the list.“If you got through No. 1 to 3, you’d be very successful through that 20-year horizon. And it just so happens that No. 1 will take you that duration to do anyway,” Rogalsky said.

Local News

KEYWORDS november 2019