Home » From wild town to ghost town: the story of Ainsworth

From wild town to ghost town: the story of Ainsworth

An old photo of Sacajawea State Park in Pasco, year unknown.

Courtesy East Benton County Historical MuseumFebruary 5, 2024

It was as wild and woolly a town that could have ever been found on the frontier.

Springing up at the confluence of the Snake and Columbia rivers, Ainsworth came before the cities of Pasco, Kennewick and Richland staked out identities.

Brawls, gunfights and social chaos were the orders of the day, with the law carried out more by vigilantes than lawmen and justice often meted out by the hangman’s rope.

But, in the late 1870s and early 1880s, the 8,000 or so laborers and railroad contractors who brought wild living to the town of Ainsworth also had a meaningful purpose – extending the Northern Pacific Railroad to Puget Sound.

For a time in its colorful, hectic heyday, Ainsworth served as the seat of Franklin County.

Ainsworth was founded in 1879, platted by Thomas Symons, a U.S. Army engineer, to serve as a depot on the Northern Pacific Railroad, as the Pend Oreille Division was seeking to connect the region between Helena, Montana, and the Columbia River.

Today, the 267-acre Sacajawea State Park is at or near the site comprising what was then Ainsworth. The park, with its trees, manicured lawns and wooded landscape, is a far cry from the experience endured by residents of the late 19th century town.

According to one description: “Ainsworth is one of the most uncomfortable, abominable places in America to live in. You can scan the horizon in vain for a tree or anything resembling one. The heat through the summer is excessive, and high winds prevail and blow the sands about into everything. By the glare of the sun and the flying sands, one’s eyes are in a constant state of winking, blinking and torment, if nothing more serious results.”

That was the landscape observed by the Lewis and Clark Expedition when it camped there on Oct. 16, 1805.

Ainsworth was named for John Commingers Ainsworth, an Oregon businessman who founded the Oregon Steam Navigation Co., among his many endeavors. Ainsworth Elementary School in Portland is named for him. Ainsworth State Park, a hikers’ and campers’ paradise in the Columbia River Gorge, is named for his son, John Churchill Ainsworth.

The railroad and the promise it held led to the founding of Ainsworth. The dusty frontier conditions with sandy, sagebrush surroundings were not particularly attractive to would-be early immigrant settlers. But America’s linkage to the Pacific Coast by the railroad showed promise for towns, ranching and a thriving agricultural industry. Attitudes began to change.

That led the Northern Pacific Railroad to select the land bordering the confluence of the two rivers for one of its new railroad towns. A sizeable number of Chinese immigrants were present, most laborers, but some ran their own businesses, like laundries and eateries.

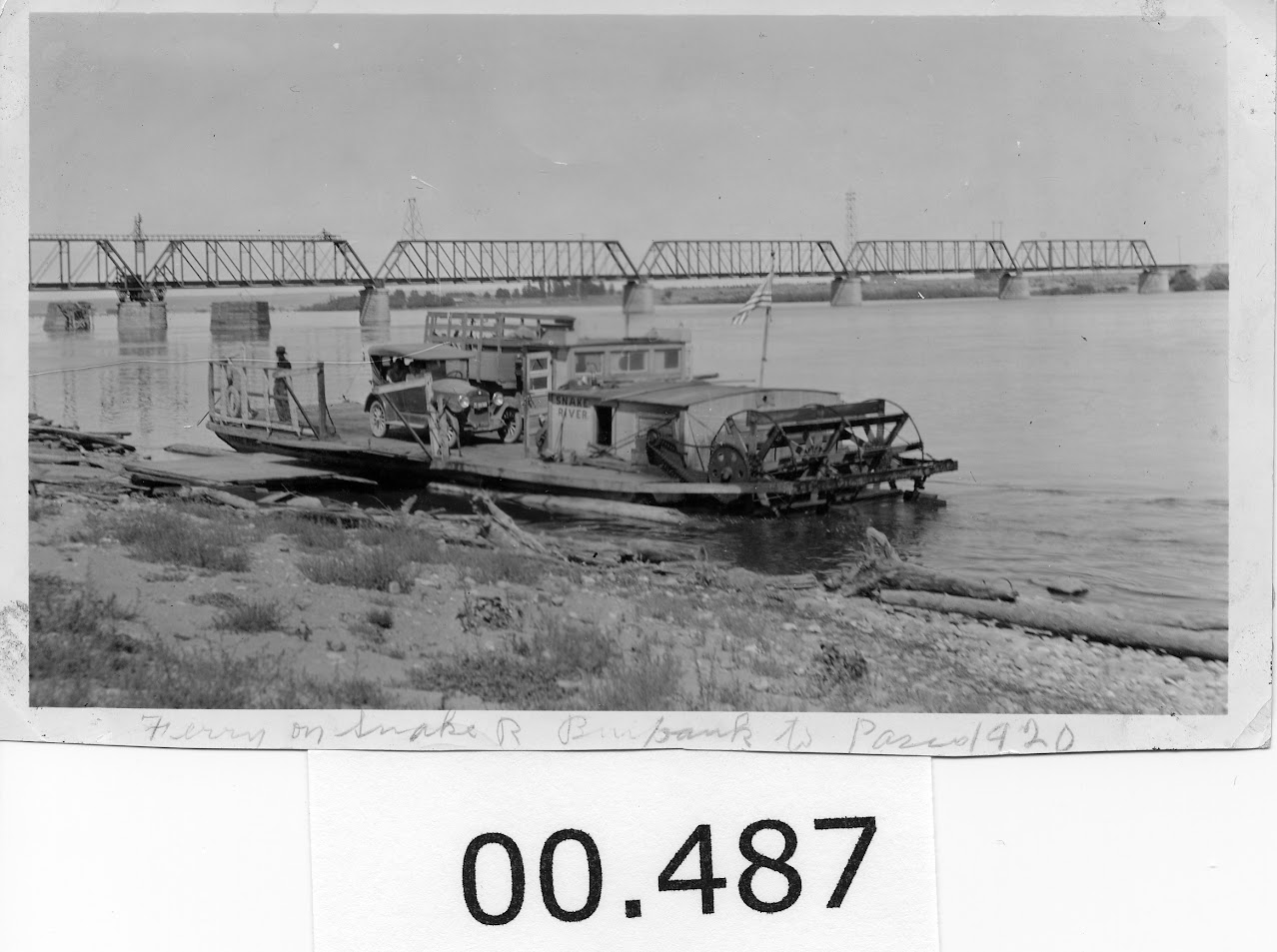

A gas-powered sternwheeler ferry beached at Ainsworth on the Snake River, taken in 1920.

| Courtesy East Benton County Historical MuseumEven though the barren, flat landscape was devoid of trees, two sawmills were built at Ainsworth by the Northern Pacific, producing lumber for construction and railroad ties. The second, built in 1881, was said to have at one time produced an estimated 65,000 to 80,000 feet of rough lumber per day.

Steamboat Capt. William P. Gray turned the rivers and Ainsworth into a flourishing steamboat trade, towing log booms to the desert flatland sawmills at Ainsworth from forests in Idaho and the Cascades and Blue mountains.

On Nov. 28, 1883, the Washington Territorial Legislature created Franklin County out of Whitman County, and Ainsworth, at the time being the largest population center in the new 1,242-square-mile county, was named county seat.

While several thousand laborers were in the Ainsworth area and used its services, one historical account said its actual maximum population was about 1,500.

The railroad bridge across the Snake River was completed in 1884, and by this time many associated with Ainsworth had grown weary of its wildness. They looked to find a new, more peaceful community.

Pasco sprang up not far away, organized in large part by Capt. Gray and the men he was associated with. Within a month, a hotel was established, as were two saloons and three places serving hot meals.

The NP founded Pasco Junction and railroading followed, including a roundhouse. The school was moved there, and much of the remaining population moved on from Ainsworth to more prosperous locations, including Pasco.

Buildings were moved to Pasco or dismantled, and the flatland community that once flourished as the raucous town of Ainsworth began returning to the sandy, sagebrush covered land it once was. By the end of the century any remnants of the once bustling community were gone. It was a ghost town.

In 1885, the Washington Territorial Legislature officially moved the seat of Franklin County to Pasco, which was incorporated on Sept. 3, 1891.

Gale Metcalf of Kennewick is a lifelong Tri-Citian, retired Tri-City Herald employee and volunteer for the East Benton County Historical Museum. He writes the monthly history column.

Senior Times

KEYWORDS February 2024