Home » Access to Tri-City health care could stand to improve

Access to Tri-City health care could stand to improve

February 18, 2020

By Patrick Jones

For several years, the greater Tri-City economy has been firing on most cylinders. Median household income has climbed 11 percent in the past five years. Local income is, and has been, higher than the U.S. median for several years, unique among Eastern Washington metros.

Wages, as measured

by the annual average, have gone up 14 percent over the same period. The two

counties employed nearly 15,000 more in 2018 than in 2014. What’s not to like?

Well, maybe trying

to see a doctor. Unlike the economy, the health care sector cannot boast of

high performance in securing access to a medical provider. Consider

Benton-Franklin Trends data on the share of adult population with a primary

care provider. In 2018, that share stood at 71 percent. This was below the Washington

state rate of 75 percent. Over time, the rate in the two counties has typically

been below that of the state. And noteworthy is that the share has actually

declined since 2012.

A hallmark of

health care reform is to provide a “medical home” for patients, anchored by a

primary care provider. In 2018, this home didn’t exist for nearly 30 percent of

local residents. Where might these patients receive care? A common “solution”

is the emergency departments of hospitals. Another, with various providers at an

outpatient facility. Yet another, not seeing any providers at all.

How might we unpack

this trend? Access to services depends on many factors. An obvious one is the

ability to pay for services, usually through health insurance. How do residents

of the greater Tri-Cities fare on insurance?

As Trends data

reveals, not so well. After some improvement after the implementation of the

Affordable Care Act, the number of residents without health insurance has risen

by over 7,000 in the last three years. Or, the rate of those without insurance

has gone up from 8.4 percent in 2016 to 10.5 percent in 2018. As the data

shows, the steepness of this increase

runs counter to experiences of the state and the U.S. Both have witnessed only

a slight increase. The rate in the two counties now stands at four percentage

points higher than Washington’s, and 1.5 points higher than the nation’s.

Why this rise? As

the data shows, the experience here isn’t too different from that of the state

or county. It’s just more pronounced. One likely cause is the repeal of

individual mandate. Another is the diminished funding for outreach. In the end,

it is hard to have a primary care provider if one doesn’t have insurance.

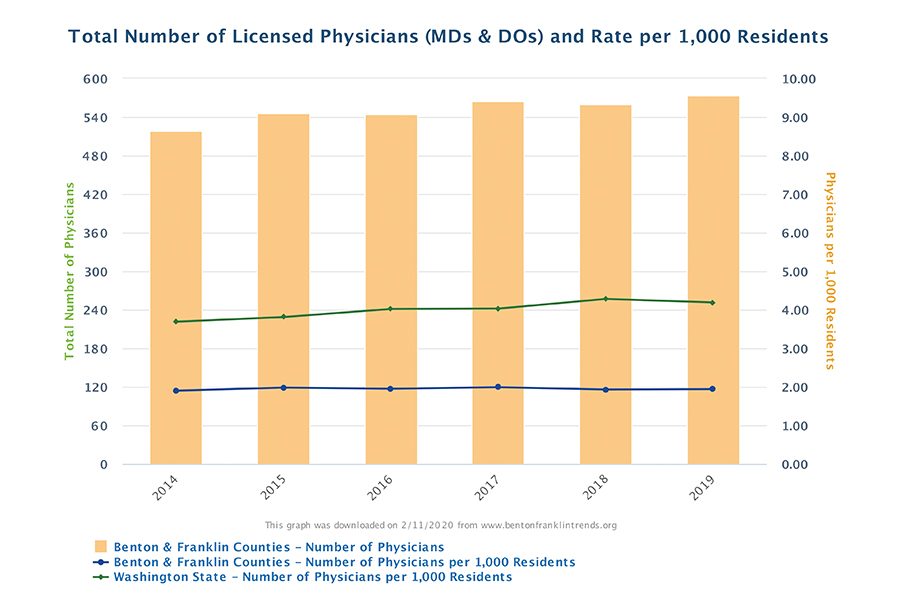

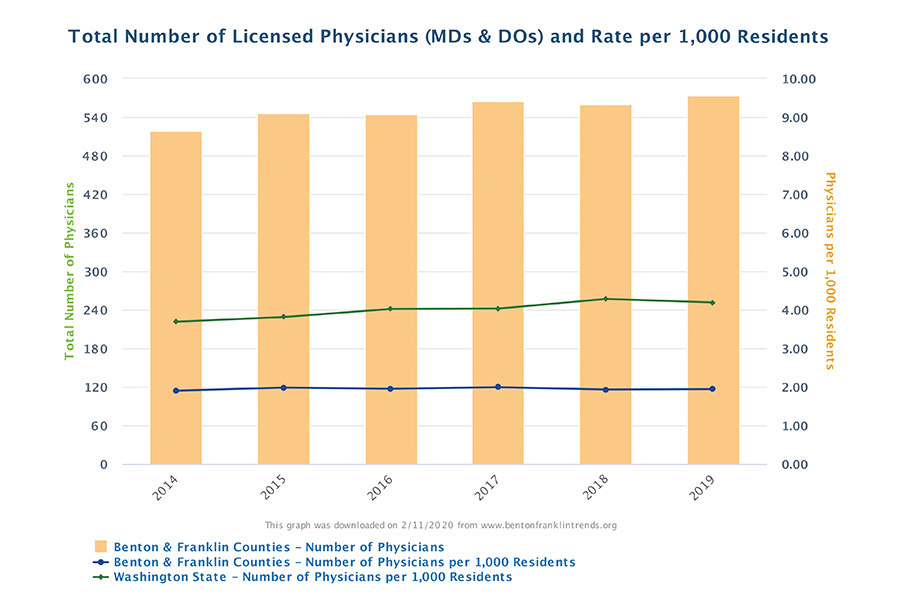

Insurance status

affects demand for medical services. The number of doctors (and more generally

of all patient-focused occupations) affects the supply of services. Trends data

shows a gain of 28 physicians in the past five years in the two counties.

That’s 5 percent and it may seem like a lot, but it is well below the population

growth of for those five years, 8 percent.

As a result,

“physician density” in the two counties remains low. The current ratio of

physicians per 1,000 residents, 1.9, is

less than half of state average! And the comparison to Washington has actually

gotten worse over time.

Why might this have

happened? One reason is obvious – the greater Tri-Cities has gained quite a few

new residents. The population’s five-year compounded annual growth rate stands

at 1.7 percent. Franklin and Benton counties rank fourth and seventh,

respectively, among all Washington counties for population growth. The more

people, the greater need for providers.

The second reason

lies in the tight spigot of Washington-trained doctors (as well as nurses and

other primary care providers). The number of graduates at the University of

Washington stood at 222 in 2018, a number unchanged for several years. Yakima’s

Pacific Northwest University has helped fill the gap, with 137 graduates in

2018, nearly double from 2015.

There is even more change

on the horizon for physicians. The Elson Floyd School of Medicine at Washington

State University should graduate its first cohort in 2021, numbering 60, and

will grow to 80. Both PNWU and WSU are likely to yield a high percentage of

students who will stay in the state and for that matter the eastern side.

What are the

consequences of constrained access to care? One lies in hospitals finance. Per

Washington state law, hospital must accept any patient who shows up at their

doors, regardless of their ability to pay. Uncompensated care from these

patients is known as charity care. This type of care among the four hospitals

in the two counties nearly doubled between 2015 and 2018, from $22.7 million to

$42.6 million.

Another consequence

is that overall health suffers. As

Trends data reveals, suicides, both levels and rates, have climbed over the

same interval. So have adult obesity and youth obesity rates.

A robust economy,

for sure. But there’s much work to be done in providing access to all

residents. Should that happen, better outcomes will follow.

D.

Patrick Jones is the executive director for Eastern Washington University’s

Institute for Public Policy & Economic Analysis. Benton-Franklin Trends,

the institute’s project, uses local, state and federal data to measure the

local economic, educational and civic life of Benton and Franklin counties.

Local News Health Care

KEYWORDS february 2020