Home » Tri-City leaders look to economy after Hanford

Tri-City leaders look to economy after Hanford

May 16, 2019

Tri-City leaders remain focused on efforts to diversify the

economy, create jobs and expand employment sectors beyond Hanford and the roles

offered by the U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors.

“TRIDEC has made this a top priority for decades,” said

David Reeploeg, vice president of federal programs at the Tri-City Development

Council.

The effort moves beyond the need to depend on Hanford as the

sole economic driver it once was. Reeploeg recalled a time when downsizing at

Hanford created a ghost town in the Tri-Cities community.

“Layoffs were incredibly disruptive in the ’80s and ’90s,”

Reeploeg said.

Since then, local community leaders in Richland are focusing

on building up its industrial center, while Pasco directs its attention to its

food processing, agricultural and distribution base, and Kennewick increases

its retail core.

“We continue to march northward with our industrial park, in

hopes of landing future employment opportunities for residents,” said Kerwin

Jensen, community development director for the city of Richland. “It’s a big

part of creating primary sector jobs in the future.”

Jensen said the city doesn’t want to focus entirely on

retail, since higher-paying jobs are the goal in the industrial center. This is

where companies like Lamb Weston, Preferred Freezer and Packaging Corporation

of America are located.

“The city of Richland wants to target north Richland as a

primary employment center,” Jensen said.

The city also is carving up smaller parcels, amounting to up

to five acres, in the portion of the city known as the Horn Rapids Business

Center, which could be used for small businesses.

Pasco has been making public investments in its

infrastructure since the mid-1990s as a way of leveraging private investment in

agricultural, distribution and processing industries. This included a

forward-thinking plan put in place 25 years ago to buy land at the north end of

the city.

“The city bought 14 (agricultural) circles, representing 640

acres. They put in a pumping facility and piping facilities and partnered with

the Port of Pasco and Franklin County and TRIDEC to establish the food

processing centers that are there now,” said Rick White, community and economic

development director for the city of Pasco.

It wasn’t just a ready-made system. Pasco had to create a

method to allow food processors to operate efficiently.

“The big obstacle in establishing the center was what to do

with all that wastewater,” White said. “They use a ton of water every day. The

volume is too much to send to the treatment plant, and would make it more

expensive for existing ratepayers who would have to pay for the expansion.”

To solve the wastewater issue, Pasco built a system to

receive the gray water, mix it with fresh water, and then chemically analyze it

for safety. Following that, the water can be safely sprayed onto the 14 circles

owned by the city, which are leased back to farmers.

“The system has been very successful and it’s at capacity,”

White said.

While they can now chalk it up to a proven success, White said

the project was a risk at the time. “I’m not sure if it was folklore or fact,

but the story goes that the first payment on the project was due one month

before the first processor signed on,” he said.

Duplicating the city’s current success isn’t as easy in

2019, as agriculture has grown into a strong economic sector. “You can’t find

farmland to buy because we’ve looked,” White said.

Even with agriculture and food processing at the core of its

economic base, Pasco still pays attention to the ebb and flow of Hanford

employment.

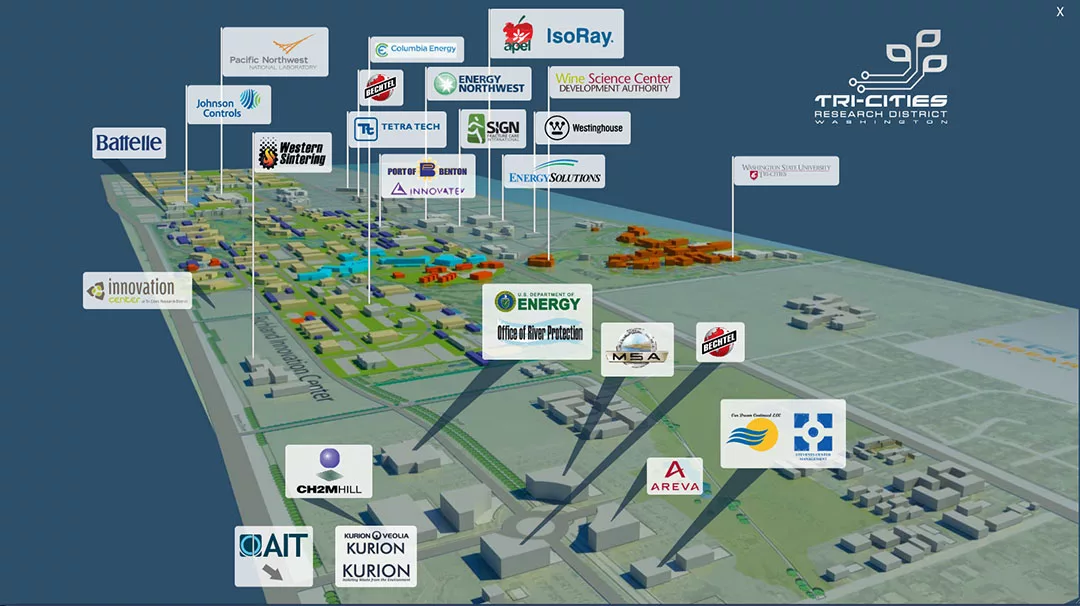

“We are a board member of the Tri-Cities Research District,

even though the majority of that activity occurs in the Port of Benton,” White

said.

The district consists of about 2,900 acres designated as an

innovation ecosystem in 2007. Its focus is on clean energy innovation and

includes the Mid-Columbia Energy Initiative, or MCEI. The initiative is

described as an effort to “focus on economic development that capitalizes on

local infrastructure, resources and expertise in the energy sector, while

retaining and recruiting businesses and jobs that promote solutions to current

and future energy challenges.”

Reeploeg said the MCEI is “uniquely positioned to grow in

that area.” This includes attracting businesses in renewable energy resources.

“We would be a good candidate for research and development

with the nuclear generation,” Reeploeg said. “(Pacific Northwest National

Laboratory) is creating new technologies every day. It’s one key element of the

economic future of the Tri-Cities.”

Richland is aware of the need to attract new residents to

fill potential jobs created by these investment opportunities.

“The workforce is tight,” said Mandy Wallner, marketing

specialist for the city of Richland’s economic development department. “We want

to recruit new people in rather than recruiting away from one local company to

another, so you’re not just creating a vacant space elsewhere.”

Wallner said with the Tri-Cities’ population soon to hit the

300,000 mark, it becomes an important threshold for attracting new businesses

in Richland and around the Tri-Cities.

“The next big piece is making sure that zoning and

infrastructure are all done in a way that’s meaningful,” White said.

Pasco’s efforts to make itself desirable to large

investments paid off with the addition of AutoZone’s 444,000-square-foot

distribution center, which opened in 2017.

“That was really an achievement,” White said. “We put the

roads in, we got it all ready, and it sat there for a long time. But then, they

came.”

White said AutoZone has the ability to expand its footprint

by 50 percent at its location.

As new jobs are created, leaders also are pressed with the

need to retain workers who are here already.

“A lot of people when they retire here, stay here, and they

need health care services,” Reeploeg said. But the cities also want to keep a

close eye on attracting the younger generation.

Wallner has noticed a cultural shift in the way people are

looking for jobs and the communities they’re moving to. “A shift from finding a

job and locating to an area, to now, ‘I want to locate to that area, then I’ll

find a job.’ ”

Reeploeg said he sees a gap in the sort of amenities that

can draw people to a large city versus a smaller metropolitan area. “We need to

continue to develop more cultural activities to retain younger workers. Current

efforts have been successful, but there’s not to say we can’t do more,” he

said.

Building on the diverse strengths of each city, the

communities are increasing their ability to create new employment opportunities

for their citizens outside of Hanford.

Any reduction in the workforce connected to a shift in the

Department of Energy project isn’t predicted to be as catastrophic as it once

was.

“It wouldn’t be as impactful as a similar change 20 to 30

years ago. There are now a lot of other economic drivers in the community, and

the community has grown,” Reeploeg said. A report commissioned by PNNL in 2009

found that since 1994, “area employment, total income, population and

residential real estate sales and building permits have increased significantly

despite very few changes to Hanford levels. The data indicate that recently the

Tri-Cities has become increasingly independent of Hanford.”

Local News Hanford

KEYWORDS may 2019