Home » Several Mid-Columbia districts earn low marks for financial health

Several Mid-Columbia districts earn low marks for financial health

May 15, 2025

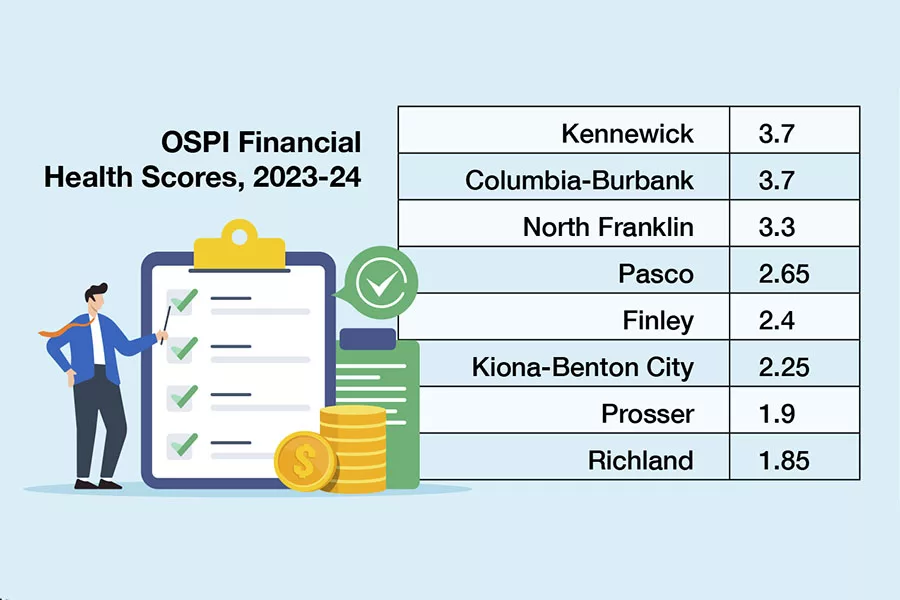

Several Mid-Columbia school districts didn’t receive high marks for their overall financial health from the state Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI).

OSPI’s financial health indicator tool shows that while three area school districts – Columbia-Burbank, Kennewick and North Franklin – have been at or above average statewide financial health scores for the past several years, five others – Pasco, Richland, Prosser, Finley and Kiona-Benton City – have consistently recorded below-average scores.

Kiona-Benton City and Richland received financial warnings from the state in the 2020-21 and 2022-23 school years, respectively, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. The districts overspent their revenues by millions and had only a few weeks’ worth of cash on hand.

OSPI develops the scores through four indicators informed by district financial reporting: fund balance to revenue, expenditures to revenue, days cash on hand, and a four-year budget summary plan. Each area is scored on a scale of 0-4, with 4 being the highest.

The overall score for all districts statewide hit a high of 3.6 in the 2020-21 school year but declined to 2.85 during the 2022-23 school year. No state average score is yet available for the 2023-24 school year.

Columbia, Kennewick and North Franklin have bucked the trend. Each posted financial health scores between 3.35 and 3.7 for the past three years, with perfect or near-perfect scores in the indicators for fund balance to revenue, expenditures to revenue, and four-year budget summary. They have maintained average scores for days cash on hand at approximately two months of expenditures.

The struggling districts, on the other hand, earned mostly zeroes for days cash on hand for multiple years, meaning they have money to cover less than a month’s worth of expenditures.

Ki-Be’s overall score of 1.55 in the 2020-21 school year triggered a financial warning from the state. Along with having less than a month’s worth of expenditures available, its expenditures exceeded revenues by more than $1.1 million and its unrestricted fund balance was 4% above its revenues.

Richland’s overall score of 1.5 in the 2022-23 school year also received a financial warning. It had about 12 days’ worth of cash on hand, expenditures exceeding revenues by nearly $6 million and an unrestricted fund balance less than 1% of its revenues.

Both district’s overall scores are higher since those years, though they are still struggling. In the 2023-24 school year, Ki-Be’s budget was still exceeding revenues by $472,768, its unrestricted fund balance was just under 5% of its revenues, and it had 12 days’ worth cash on hand.

Richland’s budget exceeded revenues by $1.5 million, its unrestricted fund balance was just over a tenth of a percent of its revenues, and it had 10 days cash on hand during the 2023-24 school year. In January 2025, the district received a $13.5 million advance on its state apportionment to mitigate cash flow challenges.

The state can take on oversight of school district budgets if a district is unable to produce a balanced budget. In that situation, OSPI can enforce binding conditions, which can include, but are not limited to, targets for the district’s fund balance, more frequent financial reporting to OSPI, regular meetings with OSPI, and counseling districts to maximize state funding by meeting legal requirements.

“OSPI’s first choice and preference is for financial challenges to be resolved locally,” the agency says on its website. “Local leaders are best situated to make the decisions that impact their students, educators, staff and families.”

Currently, school districts also can avoid being placed under binding conditions by making interfund loans that exceed their negative fund balance. Such interfund loans are usually when money is moved from one of the district’s restricted funds, such as for capital projects, to the general fund, with the district committing to paying back that money with interest.

Latest News Local News Education & Training

KEYWORDS May 2025

Related Articles

Related Products