Home » What happens to the spent fuel SMRs will produce?

What happens to the spent fuel SMRs will produce?

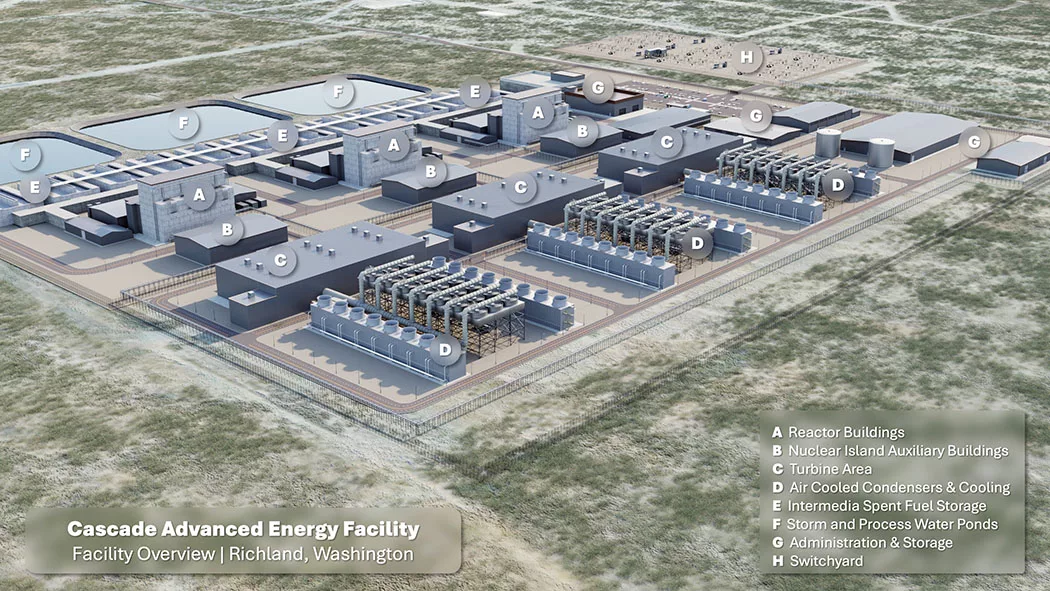

A schematic of the proposed Cascade Advanced Energy Facility identifies the different components of the facility that will house small modular reactors, or SMRs, and other support components.

Courtesy AmazonDecember 12, 2025

Nuclear power had never supplied as much electricity to the world as it did in 2024. More than 2,660 terawatt-hours was produced, enough to cover the energy needs of India alone.

Seven new reactors came online that year, including one in the United States, with dozens more in various stages of design or construction, according to the World Nuclear Association.

The planned Cascade Advanced Energy Complex with four initial small modular reactors, or SMRs, outside of Richland is one of the future new nuclear power providers that nuclear power advocates say is needed to secure the world’s energy future.

“The new record set for nuclear generation marks a rallying point and a call to action. The challenge ahead is immense, but so is the opportunity,” said Sama Bilbao y León, the association’s director general, in a statement. “With the backing of bold global industry leaders, forward-thinking governments, and an increasingly engaged public, the path to tripling nuclear capacity is not only achievable; it is necessary.”

But that energy future will come with challenges: the radioactive spent fuel used to create it.

“There’s a lot of people in the nuclear industry who pretend it isn’t a problem,” Seth Kirshenberg, executive director of Energy Communities Alliance, which represents the interests of communities impacted by U.S. Department of Energy facilities, told the Tri-Cities Area Journal of Business.

The nation’s commercial nuclear reactors have generated the bulk of the nation’s more than 90,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel. Currently, spent fuel is stored on-site as long as the facility remains in operation.

At Energy Northwest’s Columbia Generating Station near Richland, spent fuel arrays are stored in a pool near the reactor for five years before being moved into concrete and steel casks that are 19 feet tall and 11 feet in diameter. More than 50 of those casks now stand in dry above-ground storage at the power plant.

Energy Northwest would take a similar approach to Cascade’s spent fuel, which will resemble billiard balls rather than the pellets of traditional arrays.

“Once spent, (the fuel) will go directly into specially designed canisters for storage where it remains until placed in a final repository,” said Kelly Rae, a spokeswoman for Energy Northwest. “Like all operating nuclear facilities, an Xe-100 (SMR) plant is designed to safely store all spent fuel for the entire 60-year operational life in one designated spent fuel storage building.”

These on-site storage arrangements were never meant to be permanent. The federal Nuclear Waste Policy Act passed by Congress in 1982 required the establishment of a national repository for the nation’s spent nuclear fuel.

That repository, once expected to be Yucca Mountain outside Las Vegas, faced intense opposition from the public as well as entities ranging from tribal to state governments. It was ultimately abandoned by the federal government in 2011.

That’s required the federal government to pay plant operators hundreds of millions of dollars per year – $11.1 billion by the end of 2024 – to mitigate the impacts of keeping fuel on site.

“An audit by the Office of Inspector General of the DOE concluded that the future liability has increased from a range of $34.1 billion to $41 billion in 2023 to a range of $37.6 billion to $44.5 billion in 2024,” according to a report from Morgan Lewis, a law firm that works in the regulatory sphere.

The lack of a permanent solution for spent fuel has led to some opposition to new nuclear development.

The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation have advocated against any nuclear energy development in the area around its reservation in northeast Oregon as well as the Cascade SMRs, which would be located on their ancestral lands in Washington state. That opposition stems from the history of impacts from the Hanford site on its people and their treaty rights.

“We recognize that the waste at Hanford, which was created by the need for arms and munitions, and the waste generated by (SMRs), is different,” the CTUIR said in a prior statement to the Journal. “However, the challenge of waste storage remains the same.”

Kirshenberg said that long-term storage of spent fuel has possible solutions, such as deep underground storage as envisioned at Yucca Mountain and similar projects being pursued by other countries for their nuclear waste.

Just as the Trump administration has made several moves over the past year to support the nuclear industry and push development forward, Kirshenberg said he expects to see draft amendments to the Nuclear Waste Policy Act to address the spent fuel storage issue.

Because in the end, it’s not the science or feasibility of those possible solutions that are the problem.

“It’s a political decision,” Kirshenberg said.

Energy

KEYWORDS december 2025

Related Articles

Related Products