Home » Programs aim to bolster nuclear tech pipeline for next generation

Programs aim to bolster nuclear tech pipeline for next generation

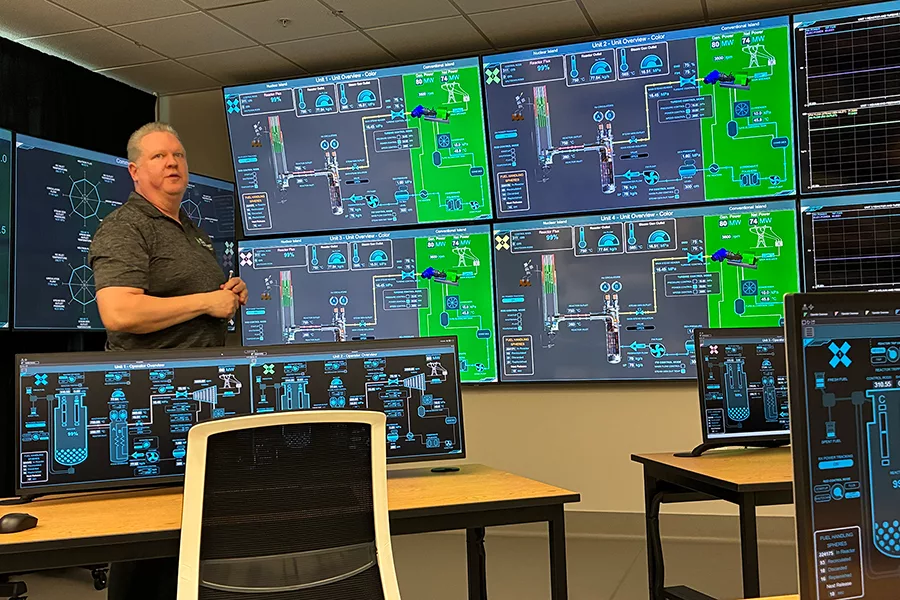

Chris Maxwell, Energy Northwest’s operations readiness manager for nuclear development, explains elements of the Xe-100 small modular reactor simulator at Washington State University Tri-Cities’ Institute for Northwest Energy Futures.

Photo by Ty BeaverNovember 13, 2025

Whenever Jesus Mota teaches a class on the top floor of Columbia Basin College’s Social Sciences & World Languages Building, with windows looking to the northeast, he asks students what they think the plumes of white rising in the distance from Energy Northwest’s Columbia Generating Station come from.

“Most of them think it’s smoke from a factory,” said Mota, CBC’s dean of career and technical education. “And that’s our biggest hurdle.”

The Pasco college has a seen a strong response to its efforts to begin building a pipeline of future nuclear workers. Its new Energy Learning Center kicked off this fall with slots for up to 40 students, which officials thought would be enough. Instead, they ended up adding a handful more due to demand.

“It filled in a day and a half and they had a waiting list,” said Sarah Fussner, Energy Northwest’s workforce development program coordinator, during an Oct. 14 panel discussion on public power organized by the Tri-City Development Council, or TRIDEC.

But maintaining that level of interest is no guarantee, officials say. Many in the Tri-Cities aren’t familiar with the role nuclear power already plays in the region or think that only those with advanced degrees in engineering and other STEM fields can have a role. And with many retiring from the nuclear industry, preparing the industry’s next generation, especially with small modular reactors, or SMRs, on the horizon, is crucial.

The Energy Learning Center was established in partnership with Energy Northwest at the beginning of 2025 as part of a $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy. It works in tandem with the college’s existing nuclear technology program, established in 1999 with support from Hanford site contractors to bolster their workforce.

The center’s goal is to respond to the “gray tsunami” of aging nuclear energy workers, from plant operators to specialists that travel around the country to work at plants during outages.

Bob Schuetz, Energy Northwest’s CEO, said typically 15% of those working outages at the generating station are first-timers. But this past spring, first-timers made up 40% of those workers, putting a strain on schedules and staff.

“That problem is real and it’s here today,” Schuetz said of the challenges with workforce development at Energy Northwest’s Public Power Forum on Oct. 23.

Specifically, the grant enabled CBC to expand from night classes taught strictly by adjunct faculty with 24 students accepted per year to the ability to serve nearly double the number of students with tenure-track faculty teaching courses during the day as well as at night. Mota says the goal is to add another 24 students at the winter 2026 term. Additionally, the grant also will support internships for CBC students at Energy Northwest to give them hands-on experience.

Students in the program will be able to train on a simulator, housed at Washington State University Tri-Cities’ Institute for Northwest Energy Futures, specifically designed to model controls for the SMRs at Energy Northwest’s planned Cascade Advanced Energy Facility. That project, announced last year, is backed by Amazon and will use a reactor model developed by X-energy.

David Schweiger, the center’s director, said recruiting into the industry is challenging because it has largely relied on hiring those who have knowledge or experience of its jobs, such as having a family member who worked in the industry. Part of the center’s work is to conduct outreach to middle and high school students about opportunities in nuclear energy.

But then comes the challenge of convincing kids that they don’t need to spend four years or more in college to be qualified for the work.

Students in CBC’s nuclear technology program can earn one-year certificates or two-year associate degrees as radiation protection technicians, non-licensed operators and instrumentation and control technicians. Those roles garner an average of $43 per hour, or $89,600 a year, in Washington state.

“One of the constant themes I hear, especially with high school kids and parents and with nuclear, is they think they need to be an engineer,” Schweiger said.

WSU Tri-Cities also is working to bolster the recruitment pipeline, with the Richland campus working to create its own six-course certificate in nuclear science. And there’s more holistic approaches such as providing opportunities for K-12 educators to learn about the region’s energy industry so they can incorporate it into curriculum.

“We’re just really excited for the opportunities coming to our university in this nuclear space,” said Kate McAteer, WSU Tri-Cities vice chancellor, during the Public Power Forum.

Higher education officials said there are still challenges ahead. Mota and McAteer acknowledge outreach to students needs to grow, especially to those living in more rural communities or from underrepresented groups in the industry, such as those from indigenous backgrounds.

There’s also the fact that construction and operation of SMRs in the Mid-Columbia is years away as Energy Northwest goes through the necessary regulatory approvals for the Cascade facility.

Students studying at CBC’s Energy Learning Center will graduate with their nuclear technology bona fides long before jobs at that facility are available. The center isn’t able to begin preparing students to support SMRs, as the reactors are not operational in the U.S. yet and training is still being developed.

But the skills the program is teaching are transferable to other energy fields, such as wind and solar, and there are roles available now for nuclear energy workers nationwide students can pursue.

Schweiger said that reaching middle and high school students now will make all the difference in the years to come. While grabbing a meal at a sandwich shop recently, he ran into a Kamiakin High School student he interacted with while promoting nuclear technology at the school. She recognized him and thanked him for what he shared.

“She said she didn’t realize all the opportunities there were,” he said.

Latest News Local News Education & Training Labor & Employment Science & Technology Workforce & Talent

KEYWORDS november 2025

Related Articles

Related Products